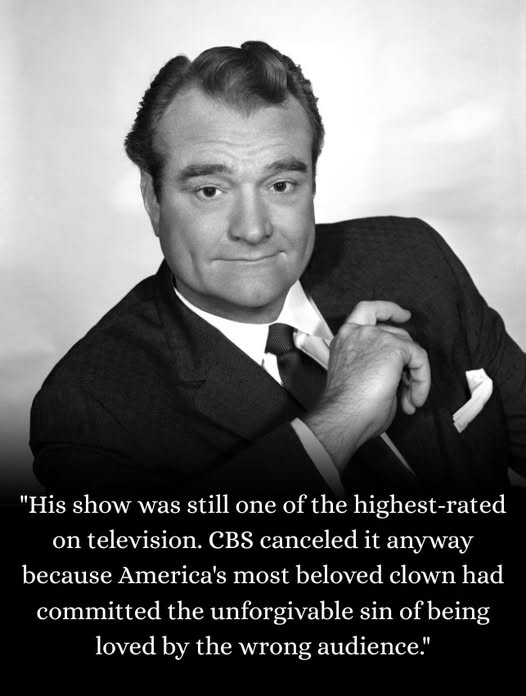

For twenty years, Red Skelton made America laugh every week.

His characters became family friends: Clem Kadiddlehopper, the country bumpkin. Freddie the Freeloader, the lovable hobo. The Mean Widdle Kid who’d declare “I dood it!” after every mischief.

Millions of families gathered around their televisions to watch The Red Skelton Hour. His physical comedy, his gentle humor, his famous pantomimes—they were appointment viewing for a generation.

Then, in 1970, CBS canceled him.

Not because his ratings were bad. They weren’t. Red Skelton’s show was still pulling strong numbers, still beloved by millions of loyal viewers.

CBS canceled him because those viewers were the wrong age.

The network had decided to chase younger, urban audiences. Traditional, family-friendly entertainment was out. Edgier content was in. In what became known as the “rural purge,” CBS axed show after show that skewed older or rural: The Beverly Hillbillies, Green Acres, Hee Haw—and Red Skelton.

It didn’t matter that audiences loved him. It didn’t matter that he’d been a fixture of American entertainment for decades. The demographics were wrong, and in television, demographics are destiny.

Red Skelton, one of the most successful comedians in television history, was suddenly obsolete—not because he’d lost his talent, but because the industry had decided his kind of humor no longer mattered.

He was 57 years old.

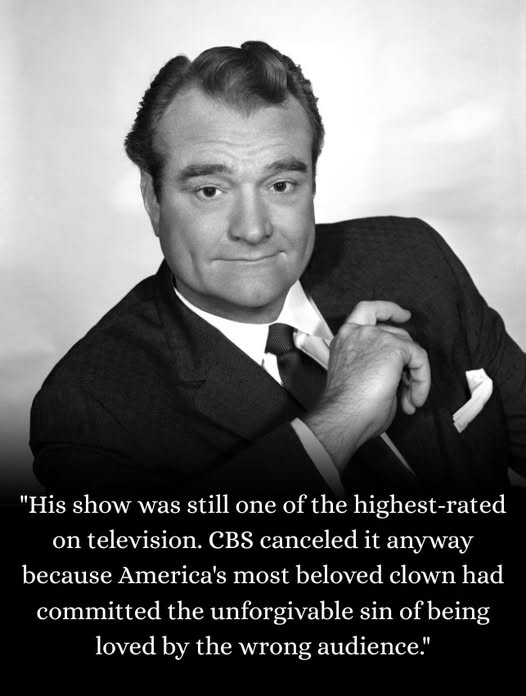

Most people would have been bitter. Most would have raged against the industry that discarded them. Red Skelton did something else entirely.

He painted.

Throughout his career, Skelton had quietly pursued art as a hobby. Now, with television behind him, he threw himself into it completely—especially paintings of clowns, the characters that had defined his life.

His clown paintings weren’t sad or ironic. They were joyful, colorful, full of the same warmth that had made his comedy so beloved. Each one captured something essential about the art of making people laugh—the vulnerability beneath the makeup, the humanity behind the performance.

And people wanted them.

Skelton’s paintings began selling for thousands of dollars each. Galleries displayed them. Collectors sought them out. The comedian who’d been deemed too old-fashioned for television found a new audience in the art world.

He also kept performing—live shows in Las Vegas, special appearances, tours where he could connect directly with audiences who still loved him. Without the constraints of network television, he could perform exactly as he wanted, for people who appreciated exactly what he offered.

In his later years, Skelton became known for something unexpected: his spoken-word performance of the Pledge of Allegiance, where he explained the meaning of each phrase with such sincerity that audiences were moved to tears. The comedian famous for physical comedy and silly characters revealed a depth of patriotism and emotion that surprised many.

Health issues—asthma and emphysema—slowed him down eventually. But Red Skelton never really retired. He painted, he performed when he could, he remained connected to the craft that had defined his life.

He died on September 17, 1997, at age 84.

The industry that had discarded him in 1970 had moved on to countless trends and fads. Most of what replaced Red Skelton on television has been long forgotten.

But his clown paintings still hang in collections around the world. His classic sketches still make people laugh. And his characters—Freddie the Freeloader, Clem Kadiddlehopper, the Mean Widdle Kid—remain beloved by everyone who remembers when television was something families watched together.

Red Skelton’s career didn’t end when CBS decided he was too old-fashioned. It just changed form.

He proved that talent doesn’t expire just because executives decide it’s out of style. He proved that creativity finds new outlets when old ones close. He proved that the connection between an entertainer and their audience is stronger than any network’s demographic strategy.

They told him family-friendly humor was finished.

He spent another 27 years proving them wrong—one painting, one performance, one laugh at a time.

Red Skelton wasn’t canceled because he stopped being good.

~

He was canceled because he never stopped being himself.

And in the end, that’s exactly what made him irreplaceable.